Earth as a Habitable World

Earth is habitable because it sits inside a very specific kind of space environment – one defined and continuously shaped by the Sun. Although we often describe Earth in terms of oceans, atmosphere, and climate, its ability to support life begins with heliophysics: the way the Sun’s light, magnetic field, charged particles, and long-term cycles interact with our planet.

Earth may look calm from the ground, but above the atmosphere is a constantly shifting boundary where solar wind meets magnetic field. Life thrives here because that boundary holds.

Earth’s magnetic shield

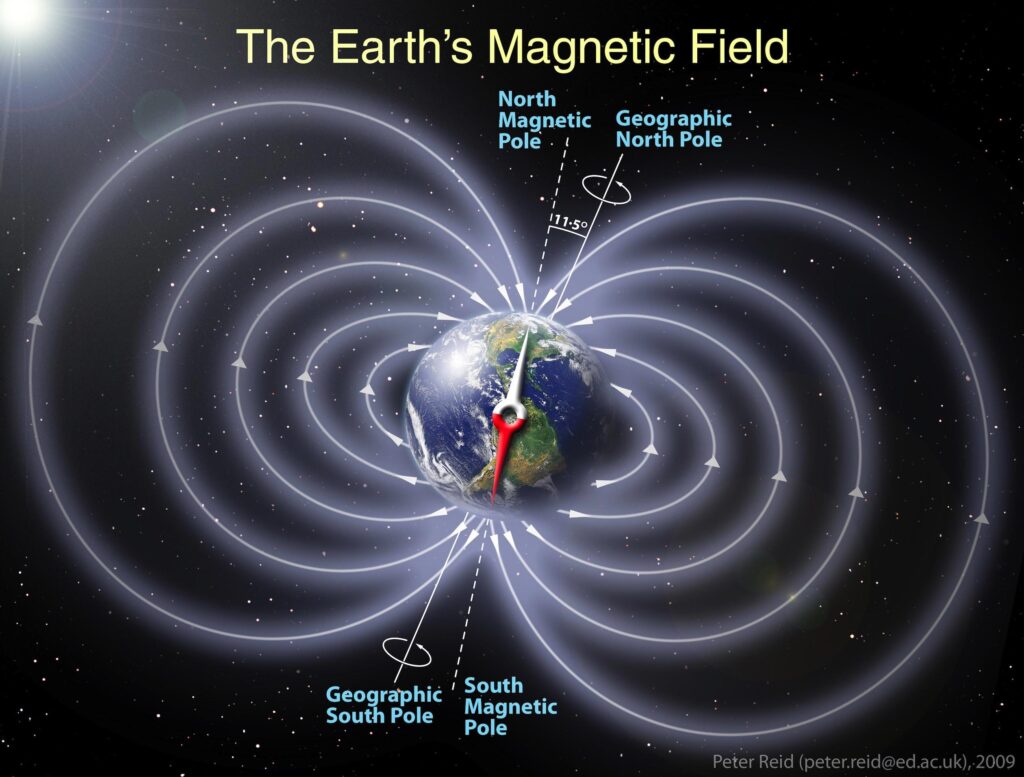

The solar wind, a stream of charged particles flowing outward from the Sun, would gradually strip away Earth’s atmosphere if it could reach the upper layers directly. Instead, it encounters Earth’s magnetosphere, a vast magnetic bubble that surrounds the planet and deflects most of the incoming particles.

As the solar wind pushes against this bubble, it stretches and compresses it, creating a dynamic environment that constantly responds to solar activity. Without this magnetic shield, the atmosphere would be eroded over time, much as it was on Mars after that planet’s global magnetic field faded. Earth’s magnetic protection is therefore not simply a geophysical feature, it is a core ingredient of habitability.

A remarkably steady star

Another reason Earth remains habitable is the type of star it orbits. The Sun is more stable than many stars its size. Its brightness varies only slightly throughout the 11-year solar cycle, and although it produces flares and coronal mass ejections, they are mild compared to the violent, frequent superflares produced by more active stars.

This stability allows Earth’s surface to maintain liquid water, moderate temperatures, and a relatively predictable radiation environment. If the Sun regularly produced large, energetic storms like those seen on many red dwarfs, Earth’s atmosphere might struggle to survive long enough for complex life to emerge.

Earth’s record of solar activity

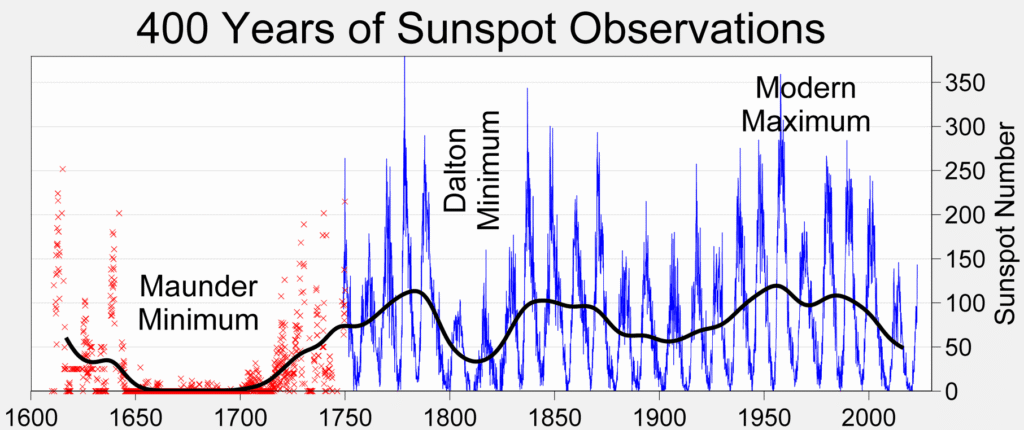

Because Earth interacts so closely with the Sun, our planet carries a natural memory of past solar conditions. When cosmic rays or high-energy solar particles collide with the atmosphere, they produce rare isotopes that become trapped in ice and absorbed by living trees. These isotopes allow scientists to reconstruct solar activity long before telescopes existed.

Tree rings preserve changes in carbon-14, which rises and falls depending on how many cosmic rays reach the atmosphere in a given year. Ice cores contain layers rich in beryllium-10, another isotope formed during cosmic-ray interactions. By reading these natural archives, we can map centuries of solar cycles, long quiet phases, and bursts of activity.

Extreme events in Earth’s past

Most solar storms never reach the ground. They are absorbed high in the atmosphere, where they cause ionisation and power the auroras. But a handful of exceptionally energetic events have been strong enough to produce measurable increases in radiation at Earth’s surface. These rare occurrences, known as ground level enhancements (GLEs), leave sharp spikes in the cosmogenic record.

The most famous examples are the so-called Miyake events around 774–775 AD and 993–994 AD. Tree rings from around the world show sudden jumps in carbon-14, suggesting that Earth was hit by extraordinarily powerful bursts of high-energy particles, far beyond anything recorded in the modern space weather era. Ice cores reveal other possible extreme events scattered through the last few thousand years.

These storms did not threaten Earth’s overall habitability, but they show the upper edge of what a Sun-like star can produce. For understanding other planets, especially those orbiting more active stars, this information is essential.

Centuries of solar variability

The Sun’s behaviour also changes on timescales longer than the standard solar cycle. Ice and tree records reveal long intervals of reduced activity, such as the Maunder Minimum in the 1600s and the Dalton Minimum in the early 1800s, as well as times of prolonged activity, like the Medieval Maximum. These shifts affect how many cosmic rays reach the planet and how Earth’s magnetic environment responds to the Sun.

None of these variations have ever made Earth uninhabitable, but they demonstrate that habitability is not just about how bright a star is, it depends on its magnetic behaviour, particle output, and long-term stability.

A planet held together by its star

Earth has remained a living world because the Sun has remained within a narrow band of behaviour, and because Earth itself possesses strong layers of protection. The magnetosphere shields the atmosphere from erosion. The atmosphere shields the surface from most radiation. And the Sun, unlike many stars, does not routinely unleash storms capable of stripping atmospheres or sterilising worlds.

To understand whether another planet can support life, we first compare it to Earth, the one example where we can study every interaction between a star and a world in detail. Earth shows us what a habitable space environment looks like, and how life can persist under the influence of a dynamic but largely stable star.

What Makes a Planet Habitable?

When scientists talk about a planet being “habitable,” they rarely mean Earth-like in a broad sense. In heliophysics and space-weather research, habitability begins with a much more focused question:

Can this world keep the conditions needed for life while orbiting the star it does?

Habitability is not just about temperature or water. It is about whether a planet can hold onto an atmosphere, withstand the star’s radiation and particle storms, and maintain stable conditions over long periods. The space environmen, the magnetic fields, stellar winds, and high-energy particles, often matters just as much as surface features.

A planet’s chances of being habitable depend on several interconnected factors, all of which tie back to its relationship with its star.

The right amount of energy

Every planet receives energy from its star. Too little, and water freezes; too much, and it boils away. This creates the classic “habitable zone,” the region where temperatures allow liquid water to exist on a rocky planet’s surface.

But in heliophysics, this is only the starting point. Two planets at the same distance from their star can experience completely different space environments. An M-dwarf may be dimmer than the Sun yet bombard its planets with extreme flares and powerful stellar winds. A Sun-like star, by contrast, provides steady illumination with mostly predictable cycles.

The Goldilocks zone is not just about warmth. It is also about energy stability, the type of radiation a star emits, and how often it produces violent outbursts.

Holding on to an atmosphere

Liquid water and stable temperatures require an atmosphere, but atmospheres are surprisingly fragile. The solar wind can erode them molecule by molecule unless something protects them.

Rocky planets have two main defences: A magnetic field, which deflects charged particles and gravity, which holds air near the surface.

If either is weak, the atmosphere becomes vulnerable. Mars offers a dramatic example. Once warmer and wetter, it gradually lost most of its atmosphere after its global magnetic field weakened. The solar wind was then able to reach the upper atmosphere more directly, allowing gas to escape into space over billions of years. A planet’s ability to remain habitable therefore depends not only on what atmosphere it starts with, but whether it can keep one while exposed to its star’s behaviour.

Radiation, particle storms, and stellar winds

The radiation environment around a planet is shaped by more than light. High-energy particles from flares and coronal mass ejections can penetrate atmospheres, ionise gases, and alter chemistry. Over long timescales, this can affect ozone layers, surface conditions, and how much harmful UV reaches the ground.

Stellar winds, the star’s constant flow of plasma, also play a major role. Stronger winds compress magnetospheres and increase atmospheric loss. Weaker winds allow cosmic rays to reach planets more easily. A planet orbiting a highly active star may face: repeated atmospheric erosion events, dramatic swings in radiation dose, and difficulty maintaining stable surface conditions.

The importance of magnetic fields

A global magnetic field is one of the strongest predictors of long-term habitability in a heliophysical sense. It acts as a shield, deflecting solar wind and charged particles and preventing atmospheric escape.

Earth’s magnetic field protects the surface so effectively that even extreme solar storms rarely affect life directly. By contrast, airless bodies like the Moon, or worlds with weak magnetic fields like Mars, experience direct exposure to solar particles and cosmic rays.

A strong magnetic field is not required for simple life, especially if it hides beneath ice or water, but it greatly enhances a planet’s ability to maintain a stable atmosphere and surface environment.

Time: The overlooked ingredient

Even if a planet meets all the criteria above, it must hold these conditions for millions to billions of years for life to gain a foothold. A planet may begin warm and wet but lose habitability quickly if:

> its star’s early flare activity strips the atmosphere,

> the radiation environment changes dramatically,

> or the planet cools or dries faster than life can adapt.

Earth’s long-term stability comes from a combination of solar steadiness, magnetic protection, and a relatively gentle space-weather environment. Other worlds may need different combinations, but all must survive the evolving behaviour of their parent star.

Habitability as a space weather question

From a heliophysics viewpoint, habitability can be summarised simply:

A planet must receive the right kind of energy from its star, and it must be able to withstand the star’s variability.

Temperature matters. Water matters. But the interaction between stellar winds, magnetic fields, radiation, and atmospheric escape often determines whether a planet remains habitable or becomes barren. Understanding these conditions on Earth lets us assess the habitability of Mars, ocean moons, and distant exoplanets.

Other Worlds in Our Solar System

Earth is not the only world shaped by the Sun’s behaviour. Every planet, moon, and small body in the solar system lives inside the same solar wind, the same magnetic field reversals, the same bursts of high-energy particles. What makes each world different is how it responds.

Some planets, like Earth and Jupiter, carry strong magnetic shields. Others, like Mars and Mercury, stand almost bare against the solar wind. Some moons hide oceans beneath ice, shielded from radiation by water instead of magnetism. And airless worlds: e.g. the Moon, asteroids, etc, experience the solar wind directly on their surfaces.

Exploring these worlds shows us how space weather determines which environments can remain stable and which are stripped, scorched, or frozen over time. The solar system becomes a laboratory for understanding the connection between stars and habitability.

Mars: A case study in atmospheric loss

Mars may be the clearest example of how a planet’s future is tied to heliophysics. Early in its history, Mars had liquid water, a thicker atmosphere, and a global magnetic field. When that field faded, the planet’s protection weakened. The solar wind began interacting directly with the upper atmosphere, slowly carrying gas away into space.

Over billions of years, this erosion thinned the atmosphere until surface water could no longer remain stable. Today the planet is cold, dry, and heavily irradiated compared to Earth. The lesson is simple: a planet can start out habitable and still lose that status if it cannot withstand its star’s long-term behaviour.

Mars shows us what happens when the balance between a star and a world tips just slightly.

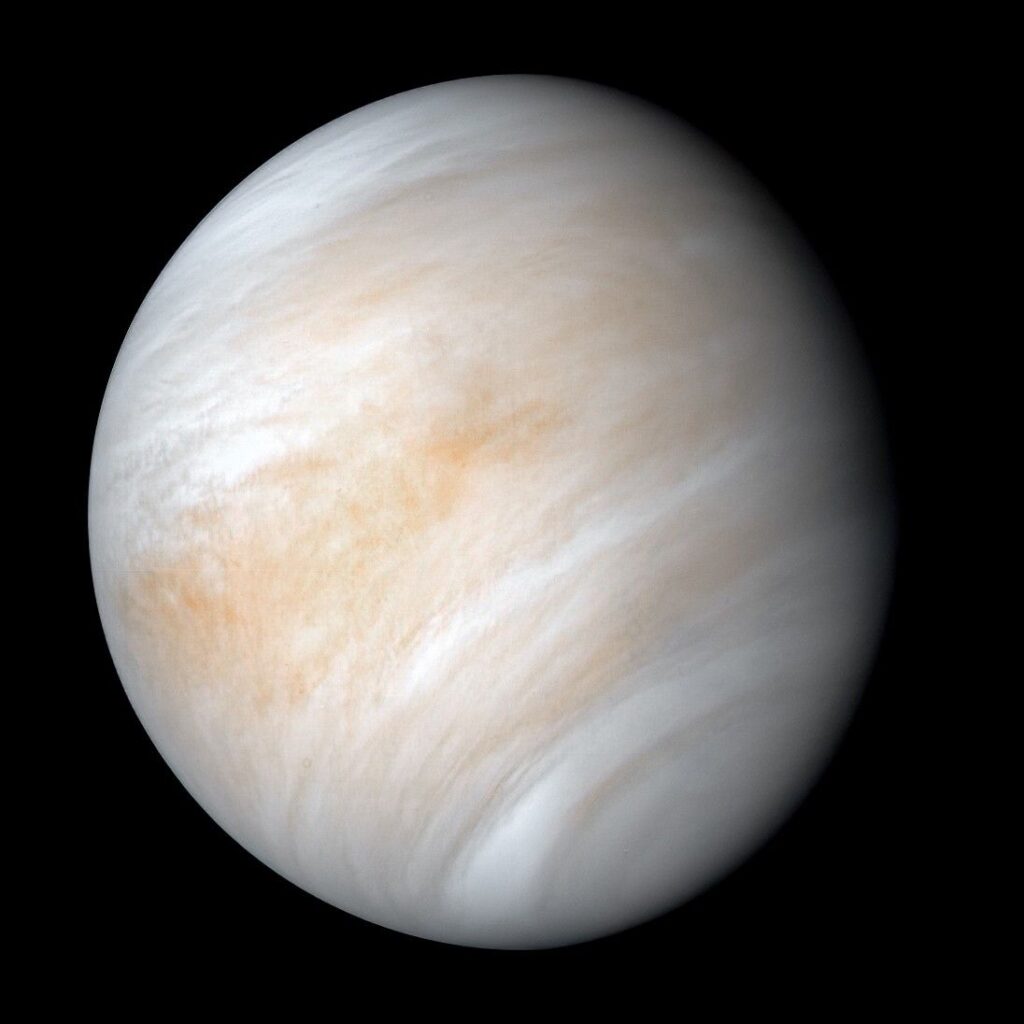

Venus: Too close to the furnace

Venus experienced a very different fate. With no global magnetic field and a position much closer to the Sun, its upper atmosphere is directly exposed to a stronger solar wind and more intense ultraviolet radiation. These conditions help drive atmospheric escape but also fuel the runaway greenhouse effect that dominates Venus today.

Venus demonstrates how stellar energy and a planet’s atmospheric response can create an uninhabitable environment even without strong solar storms. Its closeness to the Sun means its space-weather environment is harsher and more dynamic, reinforcing the idea that habitability depends on more than distance alone.

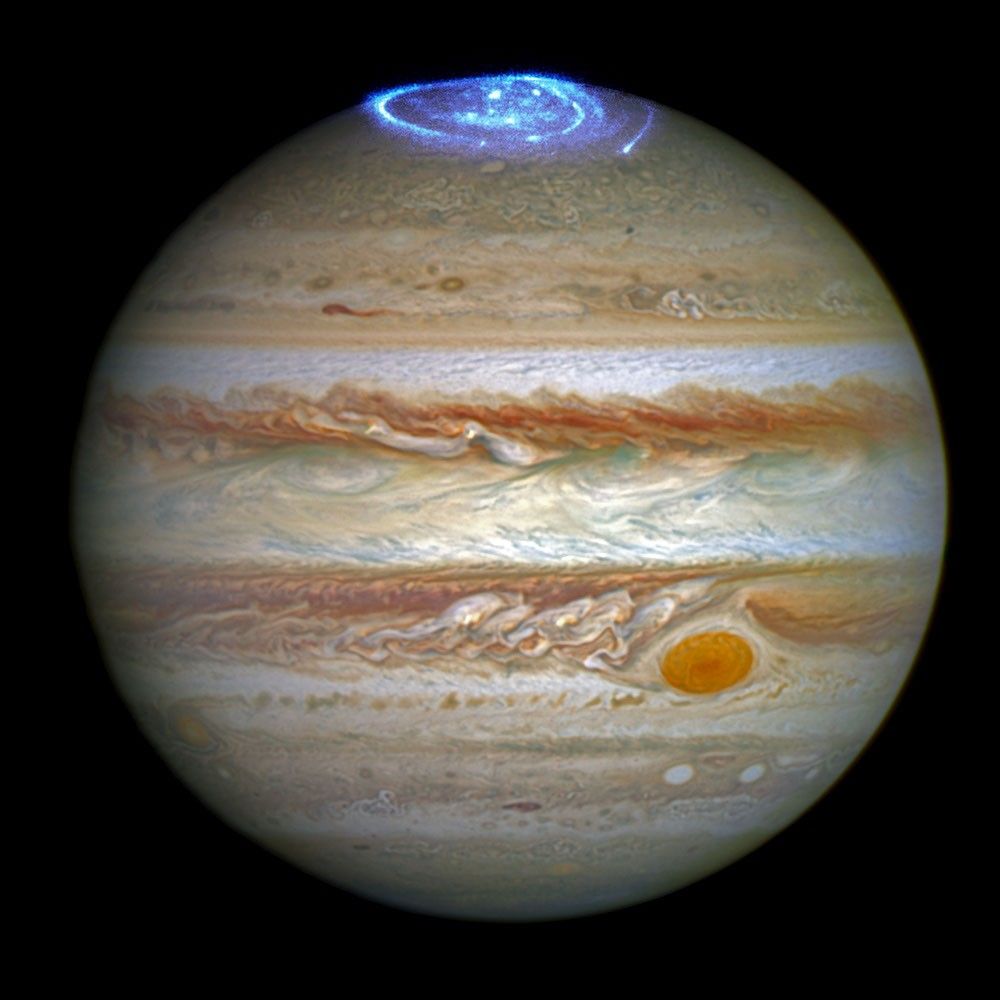

Jupiter and Saturn: The giants of magnetism

The gas giants have magnetic fields so immense that they create magnetospheres larger than the Sun itself. Jupiter’s magnetosphere is the largest single structure in the solar system aside from the heliosphere. These vast magnetic bubbles trap charged particles and create intense radiation belts that dwarf Earth’s Van Allen belts.

Jupiter’s auroras shine constantly, powered not only by the solar wind but by the volcanic activity on its moon Io, which pumps material into the giant planet’s magnetic environment. Saturn’s auroras are gentler but still far brighter than Earth’s.

These worlds are not habitable, but their magnetospheres teach an important lesson: magnetic fields do not always protect. They can also trap radiation, amplifying hazards for any nearby moons or spacecraft.

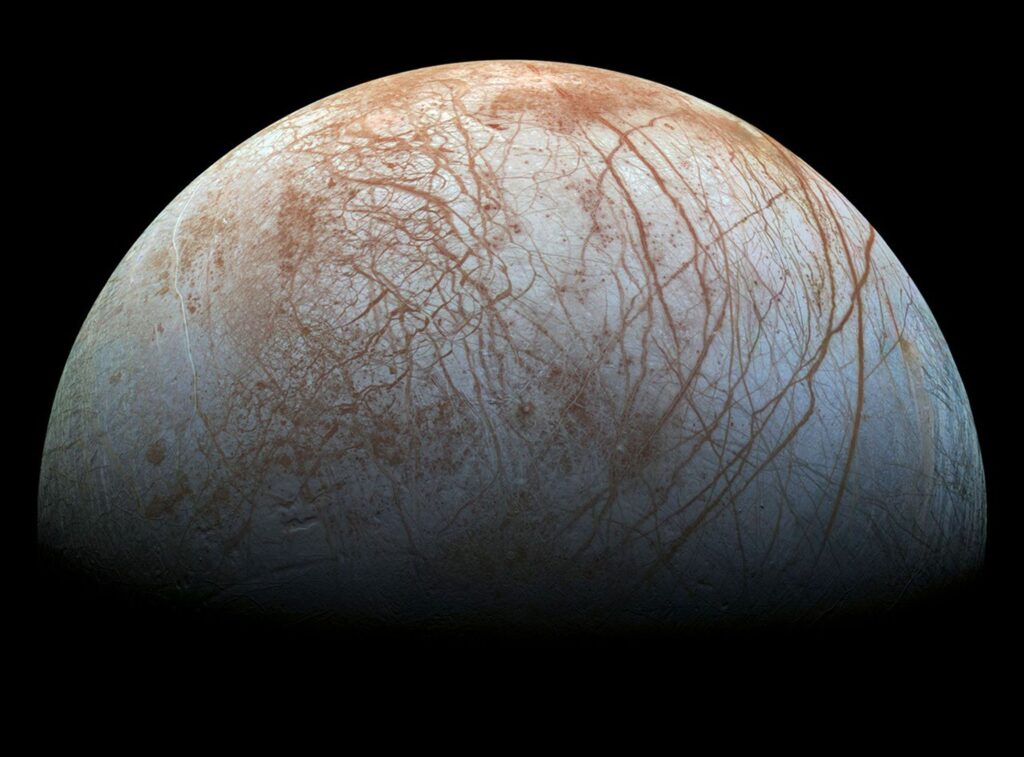

Icy Moons: Protected worlds beneath the surface

Europa, Enceladus, and other icy moons are exposed to harsh radiation at the surface, particularly near Jupiter. Yet beneath their ice shells lie dark oceans warmed by tidal heating rather than sunlight. Their habitability depends less on solar energy and more on insulation, layers of ice that shield their subsurface environments from radiation and the solar wind.

In these cases, the Sun’s influence shapes the surface, but the potential habitats lie far below protected by water and ice. These moons expand our definition of where life might exist, and show that space weather does not simply destroy habitability but can also push it underground.

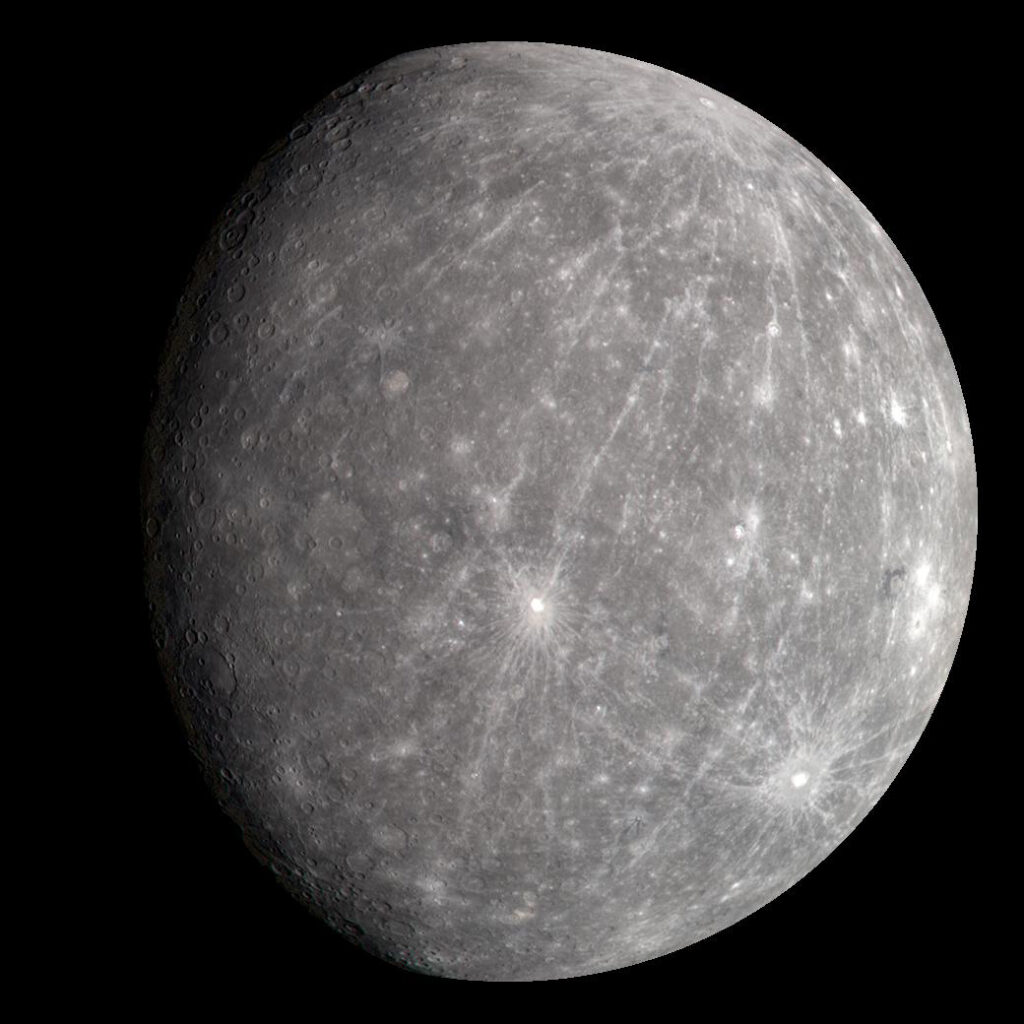

Airless Worlds: Direct exposure to the solar wind

Bodies like the Moon, Mercury, and most asteroids lack both atmospheres and magnetic fields. With no shield, they are directly exposed to the full force of the solar wind. Charged particles implant themselves in the soil, charge the surface electrically, and gradually modify the top layers of rock.

These environments are far from habitable, but they offer a perfect demonstration of how raw space weather shapes a world. They also show what happens when nothing stands between a planet and its star.

A Solar System of experiments

Seeing how different worlds respond to the same Sun gives us a range of outcomes: Mars losing its atmosphere, Venus heating beyond recovery, Jupiter generating radiation stronger than the solar wind itself, and icy moons maintaining sheltered oceans in complete darkness.

Each world sits somewhere along the spectrum of habitability, not in terms of biology, but in terms of how well it withstands or adapts to the space environment around it.

These natural experiments help us evaluate distant exoplanets. If a world resembles Mars in size and mass but orbits a far more active star, atmospheric loss may be inevitable. If a planet sits deep in a giant’s magnetosphere, radiation may be extreme. If a planet lacks a magnetic field, its survival depends on atmospheric thickness and distance from its star.

Habitability and other stars

A planet’s star is the most important factor in determining whether it can support life. Stars are not quiet background lights, they are active engines. They flare, spin, brighten, dim, and launch storms into space. Every world in the universe lives inside the space environment created by its parent star (or stars!), and habitability depends on how well a planet can survive that environment. Earth is fortunate to orbit a star that is, by stellar standards, unusually steady. Many other stars deliver far more extreme conditions.

The Star’s magnetic personality

All stars have magnetic fields generated by the motion of hot plasma in their interiors. As these magnetic fields tangle and reconnect, they produce flares, coronal mass ejections, and bursts of energetic particles. But not all stars behave the same way.

Smaller stars, especially red dwarfs (M-dwarfs), have stronger magnetic activity relative to their size. They flare more often, more violently, and sometimes unpredictably. A single flare from an active M-dwarf can release more energy than the Sun emits in an entire day.

These outbursts can send intense ultraviolet radiation, X-rays, and highly energetic particles toward orbiting planets. For many worlds, this is the defining limit of habitability.

How stellar winds shape planets

Every star produces a stellar wind: a stream of charged particles flowing outward in all directions. The power of this wind determines how much pressure it exerts on planetary magnetospheres and upper atmospheres.

A strong stellar wind can compress a planet’s magnetic field and make it easier for atmospheric gases to escape. Over millions of years, even a modest increase in wind strength can thin or remove an atmosphere entirely.

This is one reason Mars, Venus, the Moon, and Mercury all look so different from Earth. Each of them orbits the same Sun, but their internal magnetic protection, or lack of it, has shaped their atmospheres in dramatically different ways.

Around other stars, especially active young stars, stellar winds can be many times stronger than the Sun’s. A planet might exist in the “habitable zone,” yet lose its atmosphere long before life ever has a chance to begin.

Stellar flares, radiation, and the question of survival

Light from stars supports life, but the high-energy radiation stars emit during flares can threaten it. Ultraviolet and X-ray radiation can break apart atmospheric molecules and disrupt ozone layers to create temporary windows where harmful radiation reaches a planet’s surface.

Particle storms, which accompany many flares, can be even more damaging. Energetic protons and heavier ions can penetrate deep into atmospheres, altering chemistry and depositing radiation at ground level. On an unprotected world, this can make the surface inhospitable. Earth experiences these events, but our magnetic field and thick atmosphere absorb most of the radiation. A planet without strong protection could be exposed to far more intense doses.

Around red dwarfs (the most common stars in the galaxy) superflares may occur frequently enough to sterilise the surface of a planet or strip its atmosphere entirely.

Magnetic fields as the first line of defence

A planet’s magnetic field plays a crucial role in shielding it from stellar storms. Earth’s field redirects charged particles toward the poles, where they create auroras rather than reaching the surface. It also prevents long-term atmospheric loss.

Mars provides the counterexample: once possessing a magnetosphere, it lost it early in its history. Without magnetic protection, the solar wind gradually eroded its upper atmosphere. Over billions of years, the planet transformed from a warm, water-rich world to the cold, thin-aired desert we see today.

This comparison shows how tightly habitability is tied to a planet’s magnetic resilience, especially around stars that produce more intense space weather than the Sun.

When Stars Decide a Planet’s Fate

Some stars are simply too active for surface habitability. Others are calm but emit too little UV light to support certain atmospheric chemistry. Still others have winds so strong that only very massive planets could retain their air.

Two planets with identical atmospheres and identical orbits can have completely different destinies depending on the behaviour of their star.

This is why modern astrobiology increasingly treats habitability as a star–planet system, not a property of planets alone. A world must coexist with its star’s brightness, radiation, particle environment, magnetic cycles, and long-term stability.

What our Sun can (and cannot) do

The Sun is not a perfectly quiet star. It flares, launches CMEs, and occasionally produces extreme events like the historical spikes recorded in tree rings and ice cores. But compared to many other stars, it rarely enters dangerous regimes.

Its magnetic cycles are regular. Its storms have upper limits. It has not produced superflares on the scale seen elsewhere in the galaxy.

This relative stability has allowed Earth to remain habitable for billions of years, long enough for complex life to evolve. When we evaluate distant exoplanets, we must ask: Does their star offer the same opportunity?

A universe of diverse space environments

Every star creates its own bubble of influence, its own version of a heliosphere. The size, shape, and turbulence of that bubble determine the radiation levels, cosmic-ray shielding, and atmospheric escape rates experienced by any planets within it.

Understanding the Sun’s behaviour gives us a starting template. But the diversity of stellar activity in the universe means that our concept of “habitable” must always be tied to space weather.

Exoplanets: Worlds around other stars

Beyond the solar system lies a vast population of planets orbiting other stars. Some circle massive blue suns; others cling close to small, dim red dwarfs; some drift in tightly packed systems, while others swing on stretched-out, lonely paths. With thousands of exoplanets now known, we can finally compare Earth’s relationship with the Sun to worlds shaped by entirely different space environments.

The first lesson is simple: planets are everywhere. The second is more important for habitability: the conditions around most stars are far harsher than the ones Earth has.

Finding other worlds

Most exoplanets are not seen directly. Instead, astronomers detect tiny changes in starlight or slight wobbles in a star’s motion. These measurements tell us a planet is there, its size, its orbit, and sometimes hints about its atmosphere.

But they also tell us how close the planet is to its star, how much energy it receives, and how strongly it could be hit by stellar winds. Even before we know what an exoplanet looks like, we can estimate the kind of space weather it experiences.

The Goldilocks Zone – and its limitations

Distance from the star matters. Too far, and liquid water freezes; too close, and it cannot survive. The “habitable zone” gives a rough boundary for where temperatures may allow water to exist. But as heliophysics shows, temperature is only the beginning. Two planets in the same habitable zone can have very different fates depending on their star’s behaviour:

> A quiet, Sun-like star may allow an atmosphere to remain intact for billions of years.

> A flare-prone red dwarf may bombard its inner planets with constant storms, stripping the air away or altering chemistry too frequently for stable conditions.

Stellar activity and atmospheric escape

Many exoplanets orbit very close to their stars, far closer than Mercury is to the Sun. At such small distances, stellar winds slam into the planet’s upper atmosphere with enormous pressure. Ultraviolet radiation breaks apart molecules and particle storms can erode the atmosphere entirely.

This process, known as atmospheric escape, is one of the central questions in exoplanet habitability research. A world may begin with oceans, clouds, and a thick atmosphere, yet gradually lose them if its star is too active or too energetic.

The solar system has already shown us this outcome: Mars is a case study in how a once-promising world can fade when magnetic protection is lost. Many exoplanets live in conditions far more extreme.

Red Dwarfs: Abundant but dangerous

Most of the stars in the galaxy are red dwarfs: small, cool, and long-lived. Their habitable zones lie close to the star, which means any planet that could have liquid water sits in a region of intense magnetic activity.

Red dwarfs produce flares that can outshine the entire star for brief moments. Some unleash superflares powerful enough to strip atmospheres or sterilise surfaces. Because their planets orbit so close, the impact is far stronger than equivalent activity from the Sun.

Yet these systems remain prime targets for habitability studies because red dwarfs are so numerous. They may host trillions of planets altogether, some with atmospheres that survive despite the challenging environment. The question is not whether life could exist there, but what defences a planet would need to endure such stars.

The role of magnetic fields in distant worlds

Just as on Earth, a strong magnetic field could help an exoplanet retain its atmosphere in the face of stellar winds. But we cannot yet measure exoplanetary magnetic fields directly. Instead, we infer them by studying atmospheric loss, auroral signatures, or how much the planet’s orbit brings it inside regions of intense stellar activity.

Some giant exoplanets show hints of powerful magnetic fields, possibly even stronger than Jupiter’s. For smaller rocky planets, the picture is still uncertain. If Earth-sized exoplanets can generate global magnetic fields, they may survive even around active stars. If not, their atmospheres may be vulnerable to erosion long before life has time to take hold.

What we can learn from their atmospheres

A few exoplanets have had their atmospheres observed directly by looking at starlight passing through them during transits. These glimpses reveal water vapour, methane, sodium, and sometimes the signatures of atmospheric escape – a world literally losing its air in real time.

The most intriguing atmospheres belong to planets that sit right on the edge: close enough to receive intense radiation, yet still holding on. These “middle-ground” worlds help us understand how much activity a star can produce before stripping its planets bare.

As our instruments improve, we will be able to study smaller, more Earth-like atmospheres, and see how common stable, long-lived environments truly are.

The galactic perspective

Every planet in the galaxy orbits inside its star’s version of a heliosphere: a bubble that protects it from cosmic rays while exposing it to its star’s own magnetic storms. Habitability depends not only on the planet and the star, but on the shape and strength of that protective bubble.

By studying exoplanets, we are discovering how rare Earth’s calm environment may be. But we are also finding that the universe is full of surprises: planets with scorched surfaces but intact atmospheres, ocean worlds beneath ice, and rocky planets that may have survived billions of years of stellar activity.

Somewhere among them may be other living worlds, shaped by their stars just as Earth is shaped by the Sun.