What is Space Weather?

Space weather describes the changing conditions in space caused by the Sun’s activity. Just as Earth has weather in its atmosphere, space has its own “weather” made up of solar wind, magnetic fields, radiation, and energetic particles. These conditions vary from day to day depending on what the Sun is doing.

At its simplest, space weather is how the Sun affects the space environment around Earth and throughout the Solar System.

Where Space Weather comes from

The Sun is constantly releasing energy and plasma into space. Most of the time this outflow, known as the solar wind, is steady and predictable. But when the Sun becomes more active, e.g. during a large coronal mass ejection, the space environment can shift quickly.

These changes create disturbances that travel through the heliosphere and interact with planets, magnetic fields, and spacecraft. This is what we call space weather.

What Space Weather is made of

The main components of space weather include:

> Solar wind: the continuous flow of charged particles from the Sun.

> Magnetic fields: carried outward by the solar wind and shaped by the Sun’s rotation.

> Radiation: including X-rays and ultraviolet light from solar flares.

> Energetic particles: fast-moving protons, ions and electrons accelerated during eruptions.

Together, these conditions determine how calm or disturbed the space environment is at any given time.

Why Space Weather matters

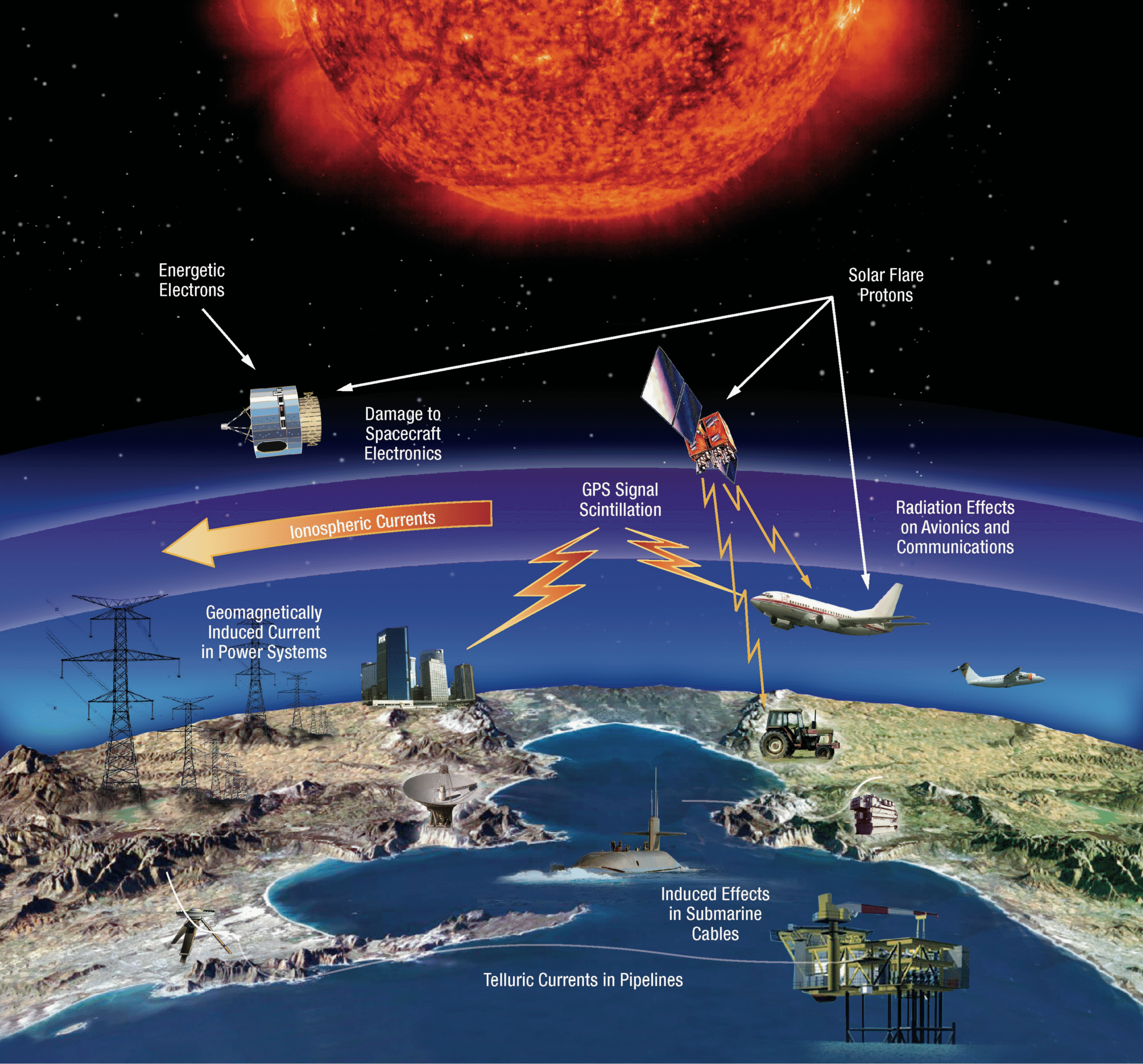

Space weather influences far more than just outer space. On Earth, it can affect radio communication, satellite operations, GPS accuracy, power grids, and astronaut safety. During strong solar events, the effects can extend across the entire planet.

It also shapes the broader solar system – altering planetary atmospheres, triggering auroras, and influencing space exploration.

Because modern technology depends so heavily on satellites and communication networks, understanding space weather is essential for protecting infrastructure and planning future human missions beyond Earth.

Space Weather is part of a larger system

Space weather doesn’t occur in isolation. It is part of the Sun’s natural variability, which is shaped by magnetic cycles, solar rotation, and the behavior of plasma in the corona. As solar activity rises and falls over the 11-year solar cycle, the intensity and frequency of space-weather events change as well.

This chapter lays the foundation for the rest of the book, which explores what drives these changes, how they travel through the solar system, and how they affect Earth and other worlds.

What Drives Space Weather

Space weather is driven by activity on the Sun. Although the Sun produces a constant outflow of charged particles called the solar wind, its magnetic field can change suddenly or dramatically, releasing bursts of energy and plasma into space. These changes form the foundation of nearly all space-weather disturbances.

This chapter outlines the main solar phenomena that influence conditions in the solar system.

The Solar Wind: The background environment

The solar wind is the baseline of space weather, a steady stream of electrons, protons, and ions flowing outward from the Sun. Its speed, density, and magnetic field vary depending on where it originates in the corona.

When these properties change, the solar wind can carry stronger magnetic fields or faster-moving streams that interact with planetary environments.

Even quiet solar wind is important: it fills the heliosphere and shapes how eruptions move through space.

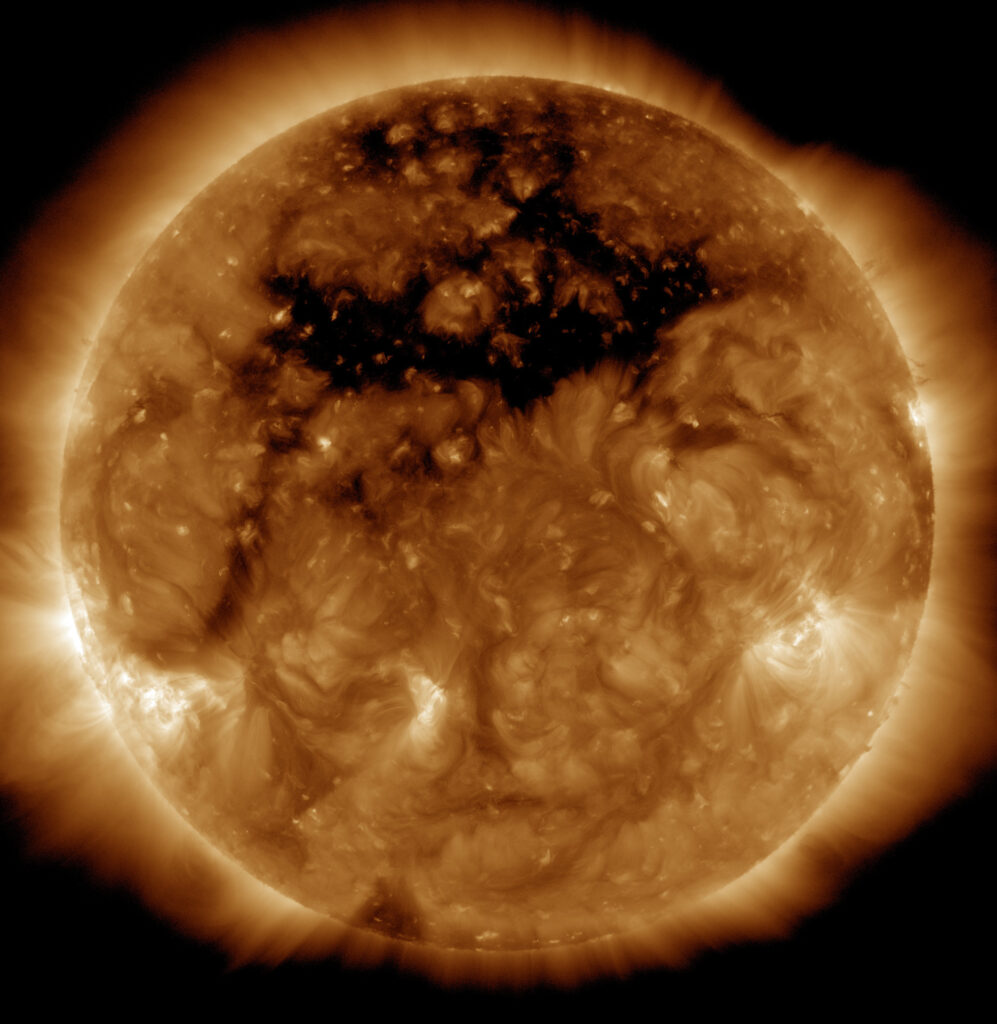

High-Speed Streams and Coronal Holes

Coronal holes are regions where the Sun’s magnetic field opens into space instead of looping back down. These areas allow solar wind to escape more quickly, producing high-speed streams (HSS).

When fast wind from a coronal hole catches slower wind ahead of it, the boundary between the two becomes compressed, forming a corotating interaction region (CIR).

CIRs and high-speed streams can cause recurrent space-weather effects, such as increased auroras and moderate geomagnetic disturbances, especially when they persist for many solar rotations.

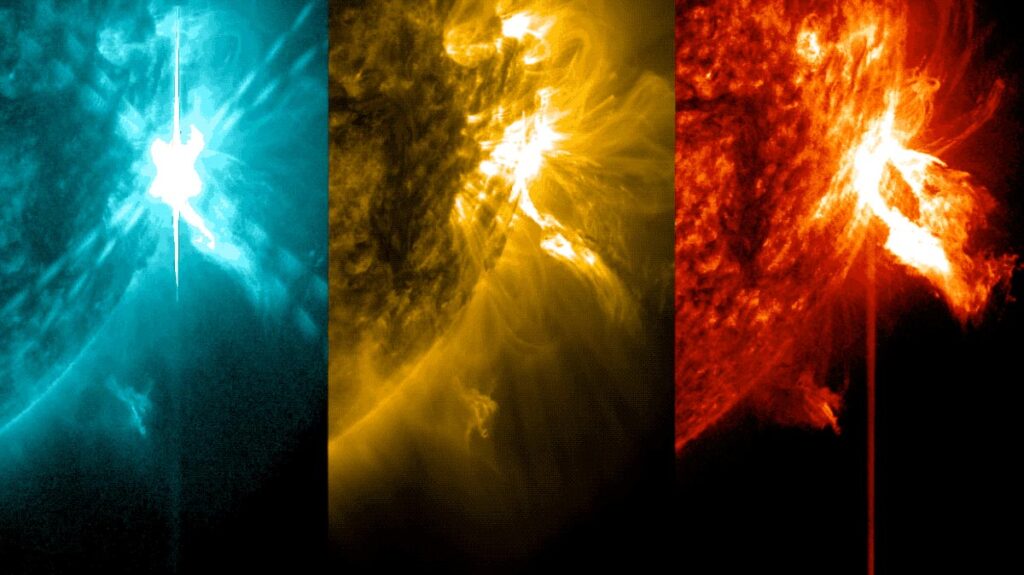

Solar Flares

Solar flares are sudden releases of electromagnetic energy caused by rapid changes in the Sun’s magnetic field. Large flares can emit radiation across the whole electromagnetic spectrum, from radio to gamma rays. Because this radiation travels at the speed of light, the effects reach Earth within minutes.

Flares are responsible for radio blackouts, and their intensity is classified on NOAA’s R-scale (R1–R5).

Flares do not necessarily produce CMEs, but they often indicate strong magnetic activity within an active region.

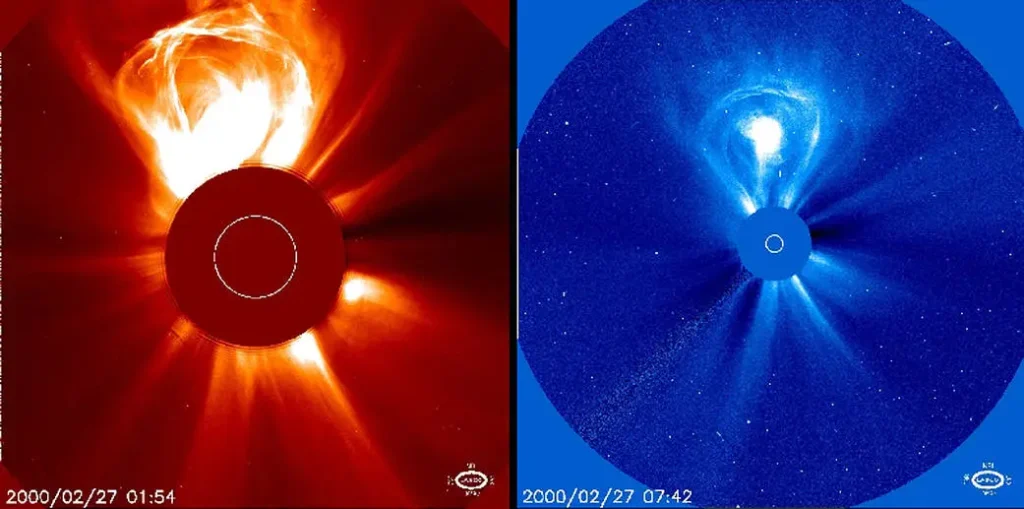

Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs)

A CME is a large cloud of plasma and magnetic field ejected from the Sun’s corona. CMEs expand as they travel and can take one to three days to reach Earth.

When a CME interacts with Earth’s magnetic field, especially if our magnetic field is southward, it can trigger geomagnetic storms, which range from mild to extreme.

These storms are classified on NOAA’s G-scale (G1–G5).

CMEs are the primary drivers of the largest space-weather events, including major auroral storms and power-grid disturbances.

Solar Energetic Particle (SEP) Events

SEP events occur when particles, mostly protons, are accelerated to very high speeds. This can happen: at the shock front of a fast CME, or directly at the flare site.

These energetic particles can reach Earth in less than an hour and can pose radiation hazards to satellites, astronauts, and high-altitude aviation.

NOAA categorizes these events on the S-scale (S1–S5).

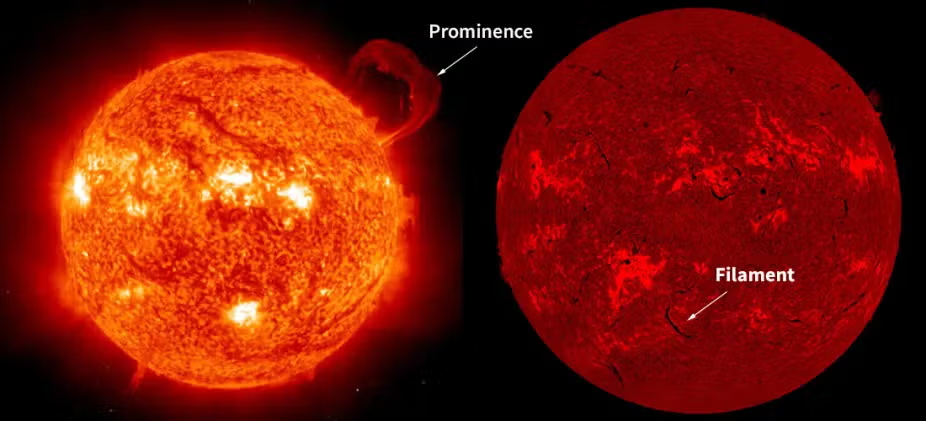

Filament and Prominence Eruptions

Filaments (seen against the solar disk) and prominences (seen at the limb) are large structures of cooler plasma suspended by magnetic fields. They can remain stable for long periods, but if the supporting magnetic field becomes unstable, they can erupt. These eruptions often form the core of a CME.

Filament eruptions are visually distinctive and can signal that a large CME may be en route.

Passive vs. Explosive Drivers

Not all solar features cause sudden disturbances. Some, like coronal holes, produce recurring, predictable influences. Others, like flares and CMEs, lead to rapid, disruptive events. Space weather arises from the combination of:

> the steady solar wind,

> the structure of the Sun’s magnetic field,

> and the sudden release of energy when magnetic fields rearrange.

Together, these solar processes create the variability we experience as space weather.

How Space Weather Moves Through the Solar System

Once solar activity leaves the Sun, it travels through a vast region filled with solar wind and magnetic fields. This environment — the heliosphere — determines how solar disturbances spread, how quickly they arrive, and how strongly they affect planets.

Space weather does not move in straight lines or simple paths. Instead, its behaviour is shaped by magnetic fields, the background solar wind, and the Sun’s rotation.

The Interplanetary Magnetic Field (IMF)

As the solar wind flows outward, it carries the Sun’s magnetic field with it, stretching it across the solar system. This extended magnetic field is called the interplanetary magnetic field, or IMF.

Its direction and strength vary depending on where the solar wind came from and what the Sun has been doing.

When the IMF reaches Earth, its orientation is especially important. A southward-pointing IMF connects more easily with Earth’s magnetic field, allowing energy to flow into the magnetosphere and increasing the likelihood of geomagnetic storms. A northward IMF, in contrast, makes strong storms much less likely.

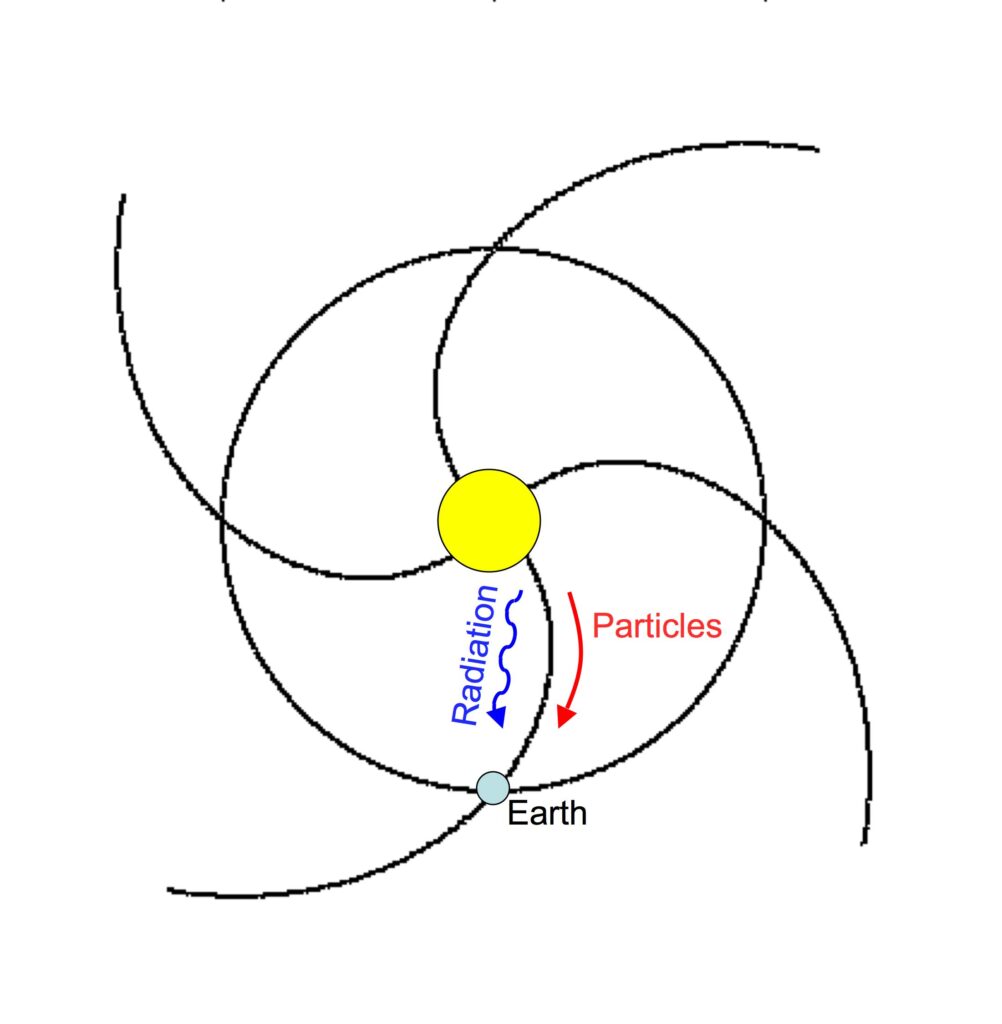

The Parker Spiral

Because the Sun rotates, the magnetic field carried by the solar wind is twisted into a spiral pattern rather than stretched straight outward. This shape — the Parker spiral — is one of the most important structures in heliophysics.

The spiral means that solar wind, magnetic fields, and disturbances sweep through space along curved paths. It also means Earth may be magnetically connected to a region of the Sun that is not directly facing us, allowing certain kinds of space weather to reach Earth even when the eruption appears off to the side.

How CMEs Travel Through Space

A coronal mass ejection expands as it moves outward, pushing aside the solar wind in front of it. If it is fast enough, it forms a shock wave that can accelerate particles and disturb the surrounding solar wind.

As the CME travels, its embedded magnetic field can rotate or change shape, and interactions with the background solar wind can deflect or compress it. By the time it reaches Earth, the CME may look quite different from how it appeared when it left the Sun.

The magnetic field inside the CME — especially whether it points northward or southward upon arrival — is often the main factor that determines how strong a geomagnetic storm will be.

How SEP Events Travel

Solar energetic particles behave very differently from CMEs. Rather than waiting for the CME itself to reach a planet, these particles travel along magnetic field lines threading through the heliosphere.

If Earth happens to be connected to the acceleration region along one of these field lines, particles can arrive in less than an hour. This is why Earth can experience a radiation storm even when the CME that created it is not directed toward us.

The Parker spiral and the level of turbulence in the solar wind control how far and how quickly these particles spread.

High-Speed Streams and Recurring Patterns

Regions of the Sun where magnetic field lines open into space — coronal holes — produce fast solar wind streams. These streams follow the Parker spiral as well, catching up with slower wind ahead of them and forming compressed regions known as corotating interaction regions (CIRs).

Because coronal holes can persist for many solar rotations, Earth may encounter the same high-speed stream every ~27 days, creating recurring intervals of moderate space-weather activity.

Why Direction Isn’t the Whole Story

A solar eruption pointing toward Earth doesn’t guarantee a strong event, and an eruption pointing away doesn’t always mean we are safe.

Radiation from flares reaches Earth regardless of direction. Particles can follow magnetic field lines even from eruptions near the limb. CMEs can rotate or be deflected on their way out. And the background solar wind can strengthen or weaken an incoming disturbance.

Space weather is therefore shaped by both the event itself and the magnetic environment it travels through.

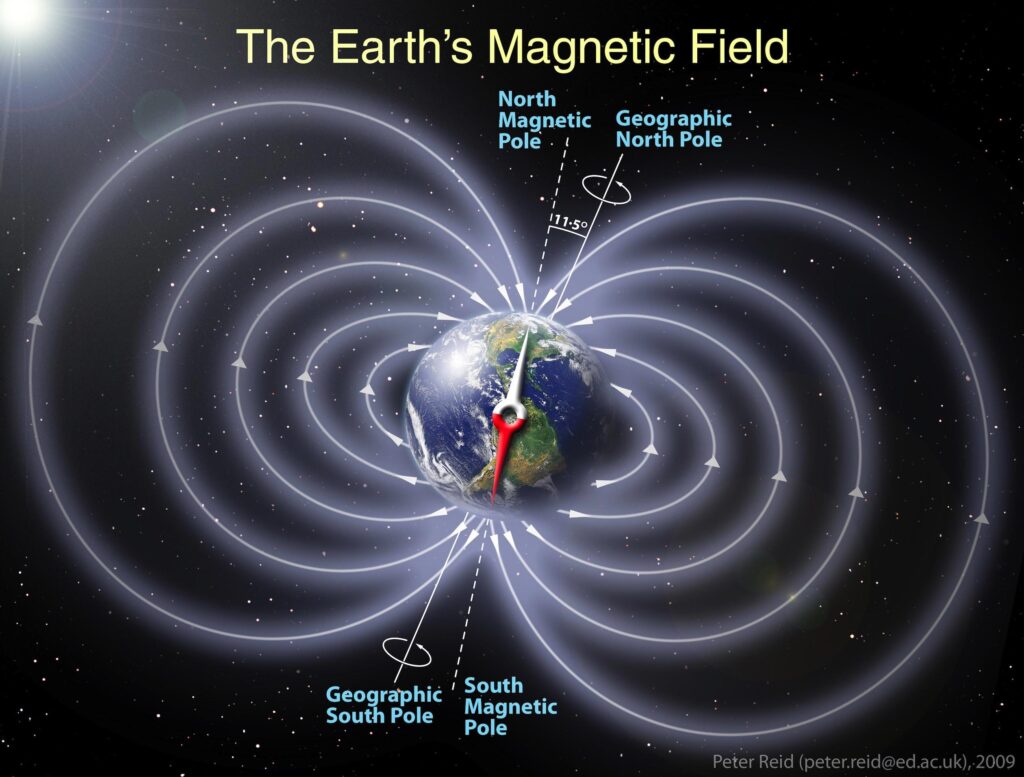

Earth’s Magnetic Field

When space weather reaches Earth, it encounters the planet’s magnetic field long before it reaches the atmosphere. This magnetic field, generated by the motion of molten metal in Earth’s outer core, creates a protective bubble around the planet known as the magnetosphere.

The magnetosphere acts as Earth’s first line of defence, guiding most of the solar wind around the planet and preventing charged particles from reaching the surface.

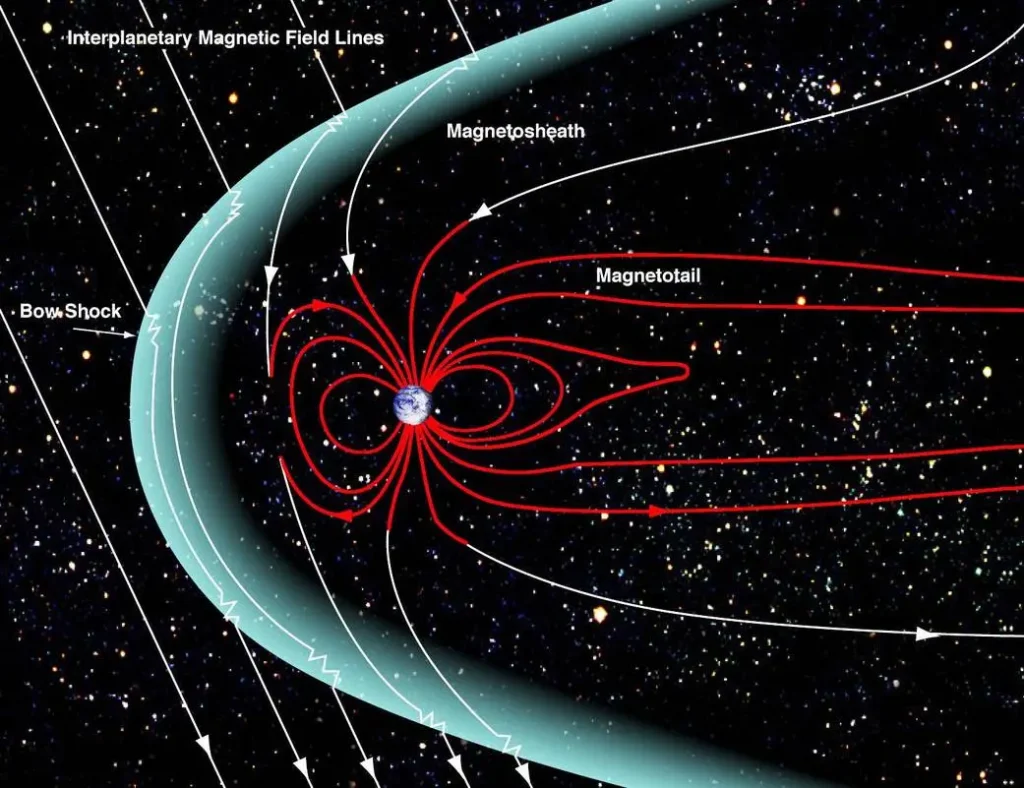

The Structure of the Magnetosphere

The magnetosphere is shaped by the solar wind. On the side facing the Sun, it is compressed into a blunt, rounded boundary. On the night side, it is stretched far into space to form the magnetotail, a long region where magnetic field lines are drawn out like a windsock.

The outer boundary where the solar wind slows abruptly is called the bow shock, similar to the wave that forms at the front of a moving ship. Behind this lies the magnetosheath, a turbulent region where solar wind and Earth’s magnetic field interact.

Inside the magnetosphere, magnetic field lines surround Earth in looping, three-dimensional structures. Some regions trap charged particles and form the radiation belts, while others act as pathways for energy to move deeper into the system.

How Energy Enters the Magnetosphere

The interaction between the solar wind and Earth’s magnetic field depends strongly on the direction of the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF).

When the IMF tilts southward, it can connect more easily with Earth’s own magnetic field. This magnetic “linking” allows energy and plasma from the solar wind to enter the magnetosphere much more efficiently. During northward IMF, this connection is weaker, and less energy is transferred.

Once energy enters the magnetosphere, it travels along magnetic field lines into the magnetotail, where it can accumulate and eventually release during periods of activity.

Processes Inside the Magnetosphere

Once solar wind energy is inside the magnetosphere, it drives a series of internal responses.

Currents strengthen around Earth, the radiation belts can swell, and magnetic field lines in the magnetotail stretch farther and farther until they eventually reconnect. This sudden reconfiguration can release energy back toward the planet, powering auroras and creating rapid changes in near-Earth space.

These processes can occur quietly or can build into larger disturbances, depending on the level of energy entering the system and the conditions in the solar wind.

Why Earth’s Magnetic Shield Matters

Without the magnetosphere, charged particles from the solar wind and from strong solar eruptions would reach the atmosphere directly, stripping it over time and increasing radiation on the surface.

Earth’s magnetic field helps preserve our atmosphere, protects biological life, and provides a safer environment for satellites, astronauts, and modern technology.

The magnetosphere also shapes how space weather affects Earth. It determines which solar events cause only minor changes and which can lead to geomagnetic storms, auroras, and disturbances in communication and navigation systems.

Geomagnetic Storms (G-Scale)

A geomagnetic storm occurs when a large amount of solar wind energy enters Earth’s magnetosphere and disrupts its normal structure. These storms are most often triggered by coronal mass ejections (CMEs), though high-speed solar wind streams from coronal holes can also cause milder, recurring disturbances. Geomagnetic storms are one of the most noticeable forms of space weather because they affect the entire magnetic environment around Earth.

How a Storm Begins

A storm usually starts when a CME arrives at Earth. As the CME pushes into the magnetosphere, it brings its own magnetic field with it. If this field is oriented southward, it can connect strongly with Earth’s northward magnetic field, allowing energy and plasma to enter efficiently.

The more sustained and strongly southward the magnetic field is, the more intense the storm will become.

Before the main impact, Earth often encounters a compressed region of solar wind ahead of the CME called the sheath. This region can itself cause disturbances, and sometimes it is responsible for the first signs of storm activity.

The Phases of a Geomagnetic Storm

Once energy is transferred into the magnetosphere, Earth’s magnetic field begins to change. The storm typically starts with a brief initial disturbance as the solar wind pressure increases.

The main phase follows, during which Earth’s magnetic field weakens as currents around the planet strengthen. This is the period when auroras intensify and can expand far from the poles.

Eventually the system recovers, returning slowly to its normal state over several hours or days.

How Storm Strength Is Measured

Many countries use the NOAA G-scale to describe the severity of geomagnetic storms. The scale ranges from G1 (minor) to G5 (extreme).

A G1 storm may cause slight fluctuations in power grids and produce enhanced auroras near the Arctic Circle.

A G5 storm can lead to strong currents in power lines, widespread transformer damage, disruptions to satellites and navigation systems, and auroras visible far into mid-latitudes.

Most storms fall within the G1 to G3 range, while G4 and G5 events are rare.

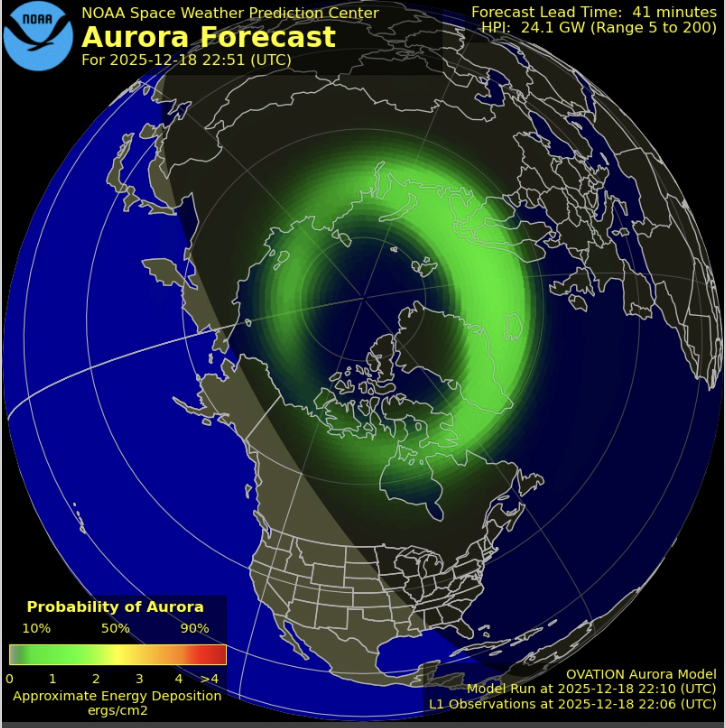

Auroras During Storms

Storms energize particles in the magnetosphere and send them spiralling down magnetic field lines toward the poles. When these particles collide with atoms in the upper atmosphere, they produce auroras.

During strong storms, the region where this interaction occurs expands equatorward, allowing auroras to be seen far from their usual locations. The colour and intensity change depending on the energy of the particles and the atmospheric gases involved.

Effects on Technology

Geomagnetic storms can cause rapid changes in Earth’s magnetic field. These changes produce electric currents in long conductors such as power lines, pipelines, and undersea cables.

Satellites may experience increased drag as the upper atmosphere expands, while communication and navigation systems can be disrupted if the ionosphere becomes highly disturbed.

Although modern systems are designed to withstand many of these effects, strong storms still pose challenges for power grid operators, spacecraft controllers, and aviation services.

Why Geomagnetic Storms Matter

Geomagnetic storms are one of the clearest examples of how activity on the Sun can influence Earth. They affect aviation, satellites, power grids, and radio communication, and they produce some of the most dramatic natural phenomena, auroras, when conditions are right.

Understanding how storms form and how strong they might become is central to space-weather forecasting and to protecting technology that depends on stable space conditions.

Auroras

Auroras are the most visible and familiar effect of space weather. They occur when charged particles from near-Earth space travel along magnetic field lines and collide with atoms in the upper atmosphere, releasing light. Normally this happens near the poles, but during strong geomagnetic storms, auroras can spread far from their usual regions and appear at much lower latitudes.

How Auroras Form

Auroras begin when electrons and ions in the magnetosphere gain energy during periods of increased solar activity. These particles spiral along magnetic field lines toward the polar regions and enter the upper atmosphere.

When they collide with oxygen or nitrogen atoms, those atoms absorb energy and then release it as light. The colour depends on the type of atom and the altitude of the collision.

Green auroras, the most common, come from oxygen around 100–150 km above Earth. Red auroras come from oxygen at higher altitudes, while nitrogen creates purple and blue shades.

Auroras During Storms

During geomagnetic storms, the amount of energy entering the magnetosphere increases dramatically. More particles are accelerated, and the region where they reach the atmosphere, called the auroral oval, expands. As a result, auroras become brighter, more dynamic, and visible much farther from the poles than usual. This is why major storms can produce auroras across Europe, the US, or even lower latitudes.

The structure of the aurora also becomes more active, showing rapid motions, curtains, arcs, and pulsating forms as magnetic fields reconfigure in the magnetotail.

Different Types of Auroras

Most auroras are created by the processes described above, but variations exist.

Discrete arcs form sharp, organised shapes along the magnetic field lines, while diffuse aurora appears as softer, widespread glows. Pulsating auroras flicker rhythmically due to changes in particle precipitation. A rarer phenomenon called STEVE looks like a thin, pinkish ribbon and is caused by fast ion flows in the upper atmosphere rather than by particle collisions in the usual way.

Auroras on Other Worlds

Auroras are not unique to Earth. Any planet with a magnetic field and atmosphere can produce them. Jupiter’s auroras are especially strong, powered both by the solar wind and by volcanic material from its moon Io. Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune also produce auroras with characteristics determined by their unique magnetic fields. Even Mars, which lacks a global magnetic field, generates auroral emissions in localised patches.

Studying auroras across the solar system helps scientists understand how planetary magnetic fields interact with the solar wind in different environments.

Why Auroras Matter

Auroras are not just atmospheric lights, they are a visible indicator of space-weather interactions. Their brightness, colour, and extent reflect how much energy is entering Earth’s magnetosphere and how active the Sun has been.

They also play a role in space-weather monitoring: sudden brightening or rapid motions can signal changes in the magnetotail or the arrival of a new surge of solar wind.

Radiation Storms and SEP Events (S-Scale)

Radiation storms occur when high-energy particles from the Sun reach the space around Earth. These particles, mainly protons, with some electrons and heavier ions, are called solar energetic particles, or SEPs.

SEP events are one of the fastest forms of space weather: depending on where they are accelerated, they can reach Earth in under an hour, long before a CME arrives.

Radiation storms are important because, unlike geomagnetic storms, they affect the space environment itself. They pose risks to satellites, astronauts, and high-altitude aviation, even if the CME that produced them never directly hits Earth.

Where SEPs Come From

There are two main ways SEPs are accelerated:

1. CME-driven shocks

A fast CME ploughing through the solar wind can drive a shock wave ahead of it. This shock efficiently accelerates particles to high energies and spreads them across a wide region of space.

These events tend to produce the largest radiation storms.

2. Solar flares

Very strong flares can also accelerate particles in the low solar atmosphere.

In many large events, both processes contribute.

How SEPs Travel to Earth

SEP transport is controlled by the structure of the interplanetary magnetic field. Particles follow magnetic field lines through the Parker spiral, so Earth can be affected even when the eruption is not aimed directly at us.

If the magnetic connection between Earth and the solar source region is strong, particles can arrive extremely quickly.

As they travel, particles scatter, spread out, and fill large portions of the heliosphere, which is why radiation storms can affect spacecraft and astronauts far from Earth.

Radiation Storm Scale (S1–S5)

NOAA uses the S-scale to describe the intensity of radiation storms.

An S1 event is minor and mainly affects high-latitude avionics.

An S5 event is extreme and can pose serious hazards to astronauts, satellites, and even aircraft on polar routes.

Most radiation storms fall into the lower categories, but large events can persist for days and significantly increase radiation levels throughout near-Earth space.

How Radiation Storms Affect Technology and People

Radiation storms can disturb spacecraft electronics, degrade solar panels, and interfere with satellite operations. Sensitive instruments may need to be placed into safe modes, and satellites in certain orbits may experience increased charging.

For human spaceflight, SEP events are one of the key hazards. Astronauts outside Earth’s protective magnetic field (for example, during lunar missions) are especially vulnerable.

At commercial aviation altitudes, radiation levels increase at high latitudes during strong SEP events, which may require rerouting of polar flights.

Ground Level Enhancements (GLEs)

A rare subset of SEP events produce particles with energies high enough to reach Earth’s lower atmosphere, where they can be detected by neutron monitors. These events are known as ground level enhancements.

GLEs are uncommon, but scientifically important, because they provide insight into the most extreme particle acceleration processes on the Sun.

Only a small number occur each solar cycle.

Why SEP Events Matter

SEP events are one of the quickest and most direct forms of space weather. They highlight how strongly the Sun’s activity can influence space environments throughout the heliosphere.

Understanding how particles are accelerated and how they travel is essential for protecting satellites, ensuring astronaut safety, and planning future missions beyond Earth’s magnetic shield.

Radio Blackouts (R-Scale)

Radio blackouts occur when solar flares emit intense bursts of X-rays and extreme ultraviolet radiation that reach Earth in minutes. Because this radiation travels at the speed of light, radio blackouts are the fastest-acting form of space weather.

They affect the ionosphere, the electrically charged region of Earth’s upper atmosphere where many radio signals travel. When the ionosphere becomes highly ionised, certain radio frequencies are absorbed rather than reflected, leading to communication disruptions.

Radio blackouts do not require a CME or a particle storm. Even when the Sun appears quiet in visible light, a strong flare can briefly disturb communication over large parts of the planet.

Why Solar Flares Cause Blackouts

When a flare occurs, it produces a sharp increase in X-ray and ultraviolet emission. These wavelengths alter the density and composition of the ionosphere almost immediately.

High-frequency (HF) radio signals, which rely on the ionosphere to bounce around the planet, are especially affected. In regions where radiation is strongest, usually on the dayside of Earth facing the Sun, signals can become weakened or vanish entirely.

Because the ionosphere recovers fairly quickly, most radio blackouts are short-lived, but even brief disruptions can impact aviation, emergency services, and long-distance communication.

R-Scale (R1–R5)

NOAA classifies radio blackouts using the R-scale, which ranges from R1 (minor) to R5 (extreme).

An R1 event may cause occasional fading of HF radio signals.

An R5 event can completely block HF communication across the entire dayside of Earth and may disrupt some low-frequency navigation systems.

The R-scale is tied directly to the strength of the flare’s X-ray emission, which is measured by satellites in near-Earth orbit. Only the most powerful flares produce R3, R4, or R5 conditions.

Impacts on Aviation and Navigation

Aviation routes over the poles rely heavily on HF radio, especially for long-range communication with aircraft. Strong radio blackouts can force flights to reroute, sometimes adding hours to travel time.

Navigation systems that depend on stable ionospheric conditions can also be affected. Although modern GPS signals are designed to minimise these effects, strong flares can still degrade accuracy until the ionosphere stabilises.

Why Radio Blackouts Matter

Radio blackouts are the most immediate reminder that activity on the Sun can affect Earth almost instantly. Even without a CME or a geomagnetic storm, a strong flare can trigger communication issues across large regions of the planet.

Understanding how flares impact the ionosphere helps forecasters predict which areas may experience interference and how quickly conditions are likely to return to normal.

Effects on Technology

Modern technology depends heavily on satellites, communication networks, navigation systems, and power infrastructure, all of which operate within or interact with near-Earth space. Because of this, space weather can have direct, measurable effects on systems we rely on every day.

Most of the time these effects are small, but strong solar events can cause noticeable disruptions, and extreme storms can challenge even well-protected systems.

Satellites and Spacecraft

Satellites orbit within regions shaped by the solar wind and Earth’s magnetic field. During geomagnetic storms, the upper atmosphere warms and expands, increasing drag on low-Earth-orbit satellites. This drag can alter orbits, requiring more frequent corrections.

Radiation storms can affect satellites in higher orbits, where energetic particles can charge surfaces, disturb electronics, or degrade solar panels. Strong events may require operators to place satellites in safe modes or limit certain operations until conditions improve.

Spacecraft traveling beyond Earth’s protective magnetic field, such as missions to the Moon or Mars, are even more exposed, and must be designed with radiation shielding and backup systems to withstand sudden increases in particle flux.

Power Grids and Ground Systems

Geomagnetic storms can induce electric currents in long conductors on Earth. Power lines, transformer stations, and even oil pipelines can experience these currents.

Most of the time the effect is small, but strong storms can push extra current into transformers, causing overheating or, in rare cases, damage.

Grid operators monitor space-weather alerts closely so they can adjust power flows, redistribute loads, or take preventive measures when strong storms are expected.

Pipelines can also experience enhanced corrosion during storms, as induced currents alter the electric environment along the metal surfaces.

Communication Systems

Radio signals interact with the ionosphere, which changes rapidly during strong solar activity.

Solar flares can ionise the atmosphere so strongly that high-frequency radio signals fade or disappear for minutes or hours on the dayside of Earth.

During geomagnetic storms, the ionosphere becomes more turbulent, causing irregularities that distort or absorb signals.

Aviation, shipping, and emergency services can be affected, especially at high latitudes where space-weather effects are strongest.

Navigation and GPS

GPS signals travel through the ionosphere, and anything that disturbs its structure can degrade accuracy.

During storms, the ionosphere can become patchy or unstable, causing delays in the signal path and reducing precision.

Most of the time this leads to small errors, but during strong storms GPS-based timing and navigation can become unreliable enough to affect surveying, precision agriculture, and some aircraft operations.

Aviation and Human Spaceflight

Radiation storms increase high-altitude radiation levels, especially over the polar regions where Earth’s magnetic shielding is weakest.

Airlines sometimes reroute polar flights to lower latitudes during strong events to reduce radiation exposure and ensure stable communication.

Astronauts in low-Earth orbit are partially shielded by Earth’s magnetic field, but missions outside this region, such as lunar exploration, must be prepared for SEP events with protective sheltering strategies.

Why These Effects Matter

Space weather influences technology quietly and continuously. Even small storms can create measurable changes, and strong events can cause widespread disturbances if systems are unprepared.

Understanding these impacts helps operators anticipate risks, design more resilient infrastructure, and make informed decisions during periods of elevated solar activity.

How We Forecast Space Weather

Forecasting space weather is the process of observing the Sun, measuring the solar wind, and using models to predict how solar activity will affect Earth.

Unlike terrestrial weather, which relies on atmospheric patterns, space-weather forecasting depends on understanding magnetic fields, plasma flows, and how disturbances travel through the heliosphere.

The goal is simple: identify what the Sun is doing, determine how it will evolve, and estimate how its effects will unfold once they reach Earth.

Watching the Sun

The first step in forecasting is continuous monitoring of the Sun. Spacecraft such as SDO, SOHO, GOES, and the STEREO satellites observe the solar surface and atmosphere in multiple wavelengths, from visible light to ultraviolet to X-rays.

These observations reveal active regions, sunspots, flares, and changes in the corona that may signal the beginning of a larger event.

Coronagraphs, instruments that block out the bright surface of the Sun, allow scientists to see CMEs as they erupt and track their speed and direction.

Monitoring the Sun also helps forecasters estimate when the next active region will rotate into view as the Sun turns once every 27 days.

Measuring the Solar Wind in Real Time

Several spacecraft sit in a special location between Earth and the Sun called the L1 Lagrange point, where they continuously measure the solar wind just before it reaches Earth.

Instruments on ACE, DSCOVR, and SOHO detect the speed, density, temperature, and magnetic field embedded in the solar wind.

Because they sit “upstream,” these spacecraft give about 30–60 minutes of warning before solar wind changes arrive at Earth.

This real-time monitoring is crucial for short-term forecasting, especially during the arrival of CMEs.

Predicting CME Arrival

Forecasting a CME involves estimating how fast it is travelling, how much it may slow down or deflect as it moves through the solar wind, and when it will reach Earth.

Models such as ENLIL simulate how the CME expands and interacts with the heliosphere. These models are updated using actual observations from spacecraft, allowing forecasters to refine arrival-time predictions as the CME moves outward.

However, one of the most difficult aspects of CME forecasting is predicting the direction of the magnetic field inside the CME. This field determines storm strength but often cannot be measured until the CME arrives at L1.

Forecasting Solar Flares and Radiation Storms

Flares cannot be predicted with the same precision as storms driven by CMEs. Forecasters monitor sunspot groups for signs of magnetic complexity, rapid changes, and growth – conditions that make flares more likely.

Similarly, radiation storms depend on how particles are accelerated by flares or CME-driven shocks and whether magnetic field lines connect the acceleration region to Earth.

Because these conditions change quickly, flare and SEP forecasts often rely on probabilities rather than definite predictions.

Understanding Earth’s Response

Forecasting space weather also involves predicting how Earth’s magnetosphere and ionosphere will react to incoming disturbances.

Models simulate how energy enters the magnetosphere, how currents around Earth will strengthen, how the auroral oval will expand, and how the ionosphere will respond.

This helps determine the likely effects on communication systems, navigation, satellites, and power grids.

Forecasters combine observations and models to create alerts for geomagnetic storms (G-scale), radiation storms (S-scale), and radio blackouts (R-scale).

Why Forecasting Matters

Space-weather forecasts are used by power-grid operators, satellite controllers, aviation authorities, astronauts, and space agencies.

They provide advance warning during strong events and help protect critical systems from damage.

As technology becomes more reliant on satellites and global communication networks, accurate forecasting becomes increasingly important – for Earth today and for future crews travelling to the Moon and Mars.

Extreme Space Weather and Historical Events

Most space-weather events are mild and pass unnoticed. But the Sun is capable of producing far stronger eruptions – events powerful enough to reshape Earth’s magnetic environment, disrupt technology, and create auroras visible far from the poles.

These rare episodes, known as extreme space-weather events, offer insight into the outer limits of solar activity and help us understand what could happen in the future.

Looking at past events shows how the Sun has affected society before – and why monitoring and forecasting are so important now.

The Carrington Event (1859)

The most famous space-weather storm occurred in September 1859. A powerful flare and CME combination struck Earth, producing auroras seen near the equator and causing telegraph systems to spark, fail, or continue operating without batteries due to strong induced currents.

Despite happening in a pre-electrical era, the Carrington storm remains a benchmark for “worst-case” scenarios.

Modern analyses suggest the CME’s magnetic field was extremely strong and arrived unusually quickly, leaving little time to prepare.

The 1921 Railroad Storm

Another major event occurred in May 1921, sometimes called the New York Railroad Storm. It caused fires at telegraph and railway stations and produced intense geomagnetic activity across much of the world.

It is considered slightly less intense than the Carrington Event but still far stronger than storms in the modern satellite era.

Quebec Blackout (1989)

In March 1989, a CME struck Earth and triggered a geomagnetic storm strong enough to collapse part of the Hydro-Québec power grid within 90 seconds.

Six million people were without power for up to nine hours. Auroras were seen across the United States and Europe.

This event reshaped how grid operators and governments think about space-weather preparedness.

The Halloween Storms (2003)

In late October and early November 2003, a series of flares, CMEs, and radiation storms struck Earth.

The Sun produced some of the most energetic X-class flares ever recorded, including an X28 event that saturated instruments.

During these storms, satellites experienced anomalies, airlines rerouted polar flights, and auroras stretched across much of North America and Europe.

These storms highlighted how multiple solar eruptions over several days can compound one another’s effects.

The Near-Miss of July 2012

In July 2012, a CME erupted from the Sun that was similar in strength to the Carrington Event.

Fortunately, it was launched from a region of the Sun that was not facing Earth, and it missed our planet by about a week.

Spacecraft at a different position in the heliosphere, including NASA’s STEREO-A, observed the event directly and confirmed its extreme intensity.

Had it been Earth-directed, it could have caused major global impacts.

Why Extreme Events Matter

Extreme storms show how powerful the Sun can be. They help scientists:

- understand the upper limits of solar eruptions,

- test and improve models,

- assess risks to satellites and power grids, and

- prepare for future events that may occur during active solar cycles.

Although events on the scale of 1859 are rare, modern society is far more dependent on technology that can be affected by space weather.

Studying past storms helps ensure we are ready for the next big one, whenever it arrives.

The Gannon Storm (2024)

In May 2024, Earth experienced the strongest geomagnetic storm in more than two decades. A cluster of fast, Earth-directed CMEs arrived in quick succession, compressing the magnetosphere and producing a long-lasting G4–G5 storm.

Auroras were seen across Europe, the United States, South America, and as far south as Mexico and the Canary Islands – regions that rarely witness auroral activity.

The storm was driven by a highly active sunspot region that produced multiple M- and X-class flares, each accompanied by CMEs that merged as they travelled through the heliosphere.

This merging created a large, complex magnetic structure on arrival, with extended periods of southward IMF – the key ingredient for strong geomagnetic storms.

Despite its intensity, the Gannon Storm caused only limited technological impacts thanks to modern grid management and early warnings. It remains one of the most significant events of Solar Cycle 25 and a reminder of how quickly multiple eruptions can combine into a major storm.

Space Weather Beyond Earth (and Around Other Stars)

Space weather isn’t unique to Earth. Every planet, moon, and spacecraft in the solar system experiences the impact of the solar wind and the Sun’s magnetic activity. And beyond our solar system, other stars produce their own space weather – sometimes far more extreme than anything our Sun generates.

Studying space weather elsewhere helps us understand how the Sun shapes the whole heliosphere and how stellar activity influences the environments of other worlds.

Space Weather at Other Planets

Each planet interacts with the solar wind differently, depending on whether it has a magnetic field, an atmosphere, or both.

Mars

Mars once had a global magnetic field, but it lost most of it billions of years ago. Without strong magnetic shielding, the solar wind can directly strip away its upper atmosphere. Over long timescales, this process has contributed significantly to Mars’s transition from a warmer, wetter world to the cold, thin-atmosphere planet we see today.

Jupiter and Saturn

Giant planets have powerful magnetic fields that create vast magnetospheres, much larger than Earth’s. Jupiter’s magnetosphere is the largest structure in the solar system aside from the heliosphere itself.

These planets also produce intense auroras, powered not only by the solar wind but by interactions with their moons. For example, volcanic material from Io feeds charged particles into Jupiter’s magnetic environment, creating auroral activity far stronger than Earth’s.

The Moon and Airless Bodies

Bodies without atmospheres or global magnetic fields, such as the Moon, Mercury, and most asteroids, are directly exposed to the solar wind and energetic particles. Surface materials can become electrically charged, and long-term exposure gradually modifies the uppermost soil layers.

Future habitats on the Moon and Mars will need to account for radiation exposure during SEP events and strong solar storms.

Space Weather for Spacecraft and Exploration

Spacecraft throughout the solar system encounter changing solar-wind conditions as they travel. Missions such as Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter experience extreme environments near the Sun, while spacecraft heading to outer planets must navigate regions of intense radiation.

Understanding space weather helps engineers design shielding, choose safe operating modes, and plan mission timelines to avoid the most hazardous conditions.

Human exploration beyond Earth’s magnetic field, including planned missions to the Moon and Mars, depends heavily on monitoring for SEP events. Even a single strong particle storm can pose serious risks during surface operations or transit.

Why Space Weather Matters for Exoplanets

Space weather also plays a major role in the habitability of planets around other stars.

Many stars, especially the common red dwarfs (M-dwarfs), produce flares far more powerful and frequent than those of the Sun.

These “superflares” can blast nearby planets with strong X-ray and ultraviolet radiation, strip atmospheres over long periods, and dramatically change surface conditions.

Even planets in the “habitable zone” may struggle to retain atmospheres if they orbit a highly active star.

At the same time, a strong planetary magnetic field might offer protection similar to Earth’s, helping preserve an atmosphere despite intense stellar winds.

Studying stellar space weather is therefore essential for understanding which planets might support life and how fragile those environments may be.

A Wider Perspective

Viewing space weather across the solar system and beyond shows that the Sun’s influence is part of a much larger story.

Every star produces its own version of space weather, shaping the environments of nearby planets and determining how they evolve.

By studying these processes close to home, we learn not only how to protect our technology and astronauts, but also how to recognise worlds that could, or could not, sustain life.